The Scottish Architect, Alexander “Greek” Thomson was born on 9th April 1817 in

Endrick Cottage in the village of Balfron, around 15 miles north of Glasgow. He was

the son of bookkeeper John Thomson and his second wife Elizabeth Cooper. Sadly,

John died in 1824 and by the following year, Elizabeth moved to the outskirts of

Glasgow with her younger children. Tragedy struck again in 1830 when Elizabeth

also died, leaving William Thomson – Alexander’s older brother – to look after his

younger siblings along with his wife, in Hangingshaw, an area near Mount Florida in

Glasgow.

By the age of 19, Thomson was an apprentice at the firm of John Baird and worked

hard to progress her career as an Architect. By age 30, he married Jane Nicholson,

and settled in a tenement at 3 South Apsley Place, near the River Clyde, with his

wife and three young children, Agnes, Elizabeth, and Alexander. In 1854, Glasgow

was blighted by an outbreak of Cholera, a disease which took the life of his first born

child Agnes, at the tender age of five. The couple went on to have two more children,

Jane and George, but unfortunately both succumbed to the disease at only 6

month’s old and sixteen month’s, respectively. Their oldest son Alexander also

became ill, and sadly died at age four years old, only three days after his infant

brother George in 1857. The epidemic had cruelly taken many lives during this time.

In early 1857, Thomson and his wife moved with their young daughter Elizabeth, to

Bute Terrace in the village of Shawlands, in a bid to escape the poor sanitation and

drinking water, and by extension, this horrible disease. These devastating

experiences of losing his children stayed with him, and influenced his opinion about

health and well-being; for example, how fresh air can combat dampness, and how

good hygiene and a clean water supply is essential. Also that the use of glass and

mirrors to bring daylight into his buildings could benefit the well-being of the

inhabitants, all things we now take for granted, he used in practical aspects in his

architectural and interior design. The move to Shawlands marked a successful

period for him professionally where he worked on some of his most well-known

buildings, including Holmwood in Cathcart – a building I know very well.

I first came to Holmwood in 2002 as a visitor with my Gran, who was a

member of the National Trust for Scotland. My interest at the time was

architectural history as well as historic interiors and I was immediately taken

by the jewel-like stencilled interiors and rich details and motifs used, not at

all like the usual Victorian style I was used to seeing. I became a volunteer in

April 2003, in what became an association of around nineteen years, during

which time I also studied at the University of Glasgow. The two Property

Managers during my time were Sally White and later, Jim MacDowell, both of

whom have sadly passed away recently; Jim in August 2022, and Sally in

January 2024. Jim was hugely influential in my decision to return to Higher

Education, and he supported my burgeoning career by offering a paid role at

Holmwood at different points during my studies, which also proved valuable

experience for my entry into employment in the heritage sector. Other

support came from the very knowledgeable staff and volunteers, in particular

two of the Volunteer Co-ordinators during my time, Bill Searil, and his

successor, Iain McGillivray. They have all made a huge contribution to this

property, and should be remembered as such, as they are very much missed.

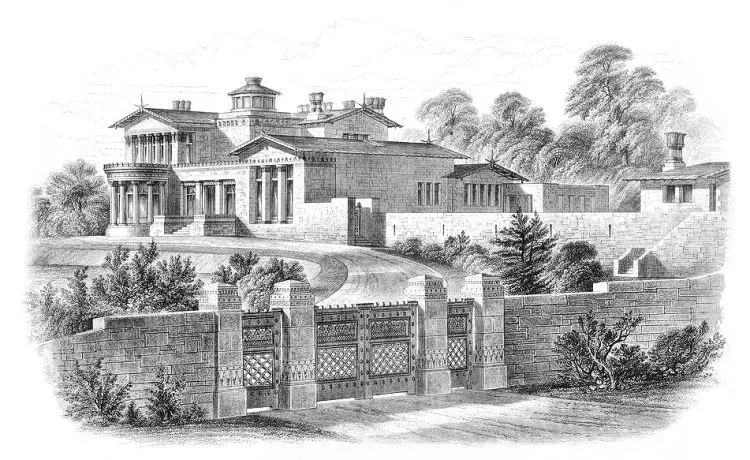

Holmwood was designed for James Couper and his wife on a fairly steep bank

overlooking the White Cart, and James and his older brother Robert’s,

Millholm paper mill below, which they owned from 1841. The five acre site

was intended for two adjacent villas to be built – one for Robert, designed by

the Architect James Smith which became known as “Sunnyside”, and the

other for James, by Thomson. I have already speculated on why the brothers

may have chosen such different architects to design each villa in my previous

post about Smith’s notorious daughter Madeleine which can be read here.

Holmwood, designed by Thomson in 1847, was intended as a fairly modest

family home. Upon approach to the front aspect of the villa through imposing

stone gate posts with wood and metal gates, the visitor is met with a

masterful illusion of a grand imposing building due, in part, to its wide

horizontal plane. This effect is created by the wall which joins the coach

house to the villa, but has the added bonus of hiding the kitchen garden from

the front view. The villa which sits at the left has an impressive circular bay

to the left where the parlour is situated and rectangular windows on the right

at the dining room. As you ascend the incline towards the front door, which is

accessed by a wide stair, you enter a square entrance which leads to a small

reception room on the left. This room is cleverly designed to have hidden air

vents in the dentil moulding to allow fresh air into the room. As the room

would have been used for leaving coats and outdoor footwear, the vents

prevent the build-up of condensation within the space – a most practical

detail when you are in an occasionally damp and dreich Glasgow! Off this

room is a second door which leads to a small toilet complete with a high level

“Shanks of Barrhead” wc and wash hand basin – lit by a frosted glass privacy

window which captures the daylight through the clear glass panelled front

door directly opposite. There is an additional detail of the frosted window

opening to allow for ventilation too as the toilet is in the centre with no

window to the outside. These very useful details are included to allow the

visitor a place to remove their outdoor clothing, and use the convenience

before they enter the main body of the house. It is a great example of how

Thomson thought about how the house would be used by those living there

and those visiting.

Once you return to the entrance vestibule, the hallway corridor is accessed

by turning left, and the visitor is rewarded by a beautifully ornate marble

horseshoe fireplace complete with zodiac symbols, a barometer with a

cherub on top, masterfully sculpted by Thomson’s friend, Mossman. The off

white marble is in stark contrast to the warm decorative palette and colourful

mosaic flooring. The hallway being set to the side of the door, rather than

immediately beyond, is another practical design feature, to prevent cold air

or leaves from the garden circulating into the main hallway corridor. The

mosaic floored hallway continues to a stairwell, top-lit by an impressive

circular etched glass starry cupola flanked by plaster chimera. At night, the

moonlight filters through the glass and creates a magical looking cascading

star decoration on the walls. As well as the entrance, there are three public

rooms where the interiors were designed with a supposedly free hand by

Thomson to embellish as he wished. Two of the public rooms are on the

ground floor; the dining room and parlour, and one is on the first floor, the

drawing room. The house has repeated motifs of Thomson’s Greek (T) key

borders, acanthus leaves, rosettes, stars and lotus, on the woodwork, floors,

fireplaces, doors and walls. Most of these motifs and colourways can be

evidenced from Owen Jones’ “Grammar of ornament” book.

The downstairs parlour was used as a daytime room, and the ceiling rose has

a sun burst to reflect the daytime activity. Whereas, the drawing room

directly above, was used in the evening – and this is reflected by the ‘starry

night’ plasterwork ceiling. But the highlight of Holmwood is surely the dining

room which has the highest height ceiling within the house. It is decorated

with a frieze depicting the stories from Homer’s Iliad – taken from illustrations

by Flaxman. There is a substantial console, used as a serving buffet with

mirrors above at roughly dado height. When you sit at the dining table, not

only does the daylight from above the console table reflect daylight around

the room, but it reflects those sitting at the table, meaning dinner guests get

to see themselves within this lavishly decorated space. As the room was used

for entertaining potential clients, I have a feeling this was done deliberately –

after all the house is designed to impress! Overall, there are too many clever,

practical and symbolic details to mention in detail in this post (the butler’s

pantry window arrangement, and the later addition of the roof over the

kitchen court for example) so I recommend you go visit this wonderful

property to see for yourself, as it is the only Thomson villa open to the public.

Information on opening days and times can be found on the National Trust for

Scotland’s page here.

Thomson died on 22nd March 1875 at 1 Moray Place, in the end terrace home

he designed for himself and family in Strathbungo, on the south side of

Glasgow. He didn’t leave his native Scotland, but he left a legacy in his will to

allow aspiring Architects to have that opportunity – as money for a travelling

scholarship. The second recipient of this award was a young Charles R.

Mackintosh.

Very interesting, I always enjoy a visit to Holmwood. Looking at your dates makes me wonder if you knew my former boss, David Alcock, who volunteered there after he retired? From about 2010, I think, until he left Glasgow a few years later.

LikeLike

Very possibly, although my wee one was born then so I had a bit of a sabbatical!

LikeLike